Once a drug lord in Los Angeles, now an activist and entrepreneur: Freeway Ricky Ross speaks about his infamous past, CIA conspiracies, and his commitment to a positive future.

By Katharina Moser

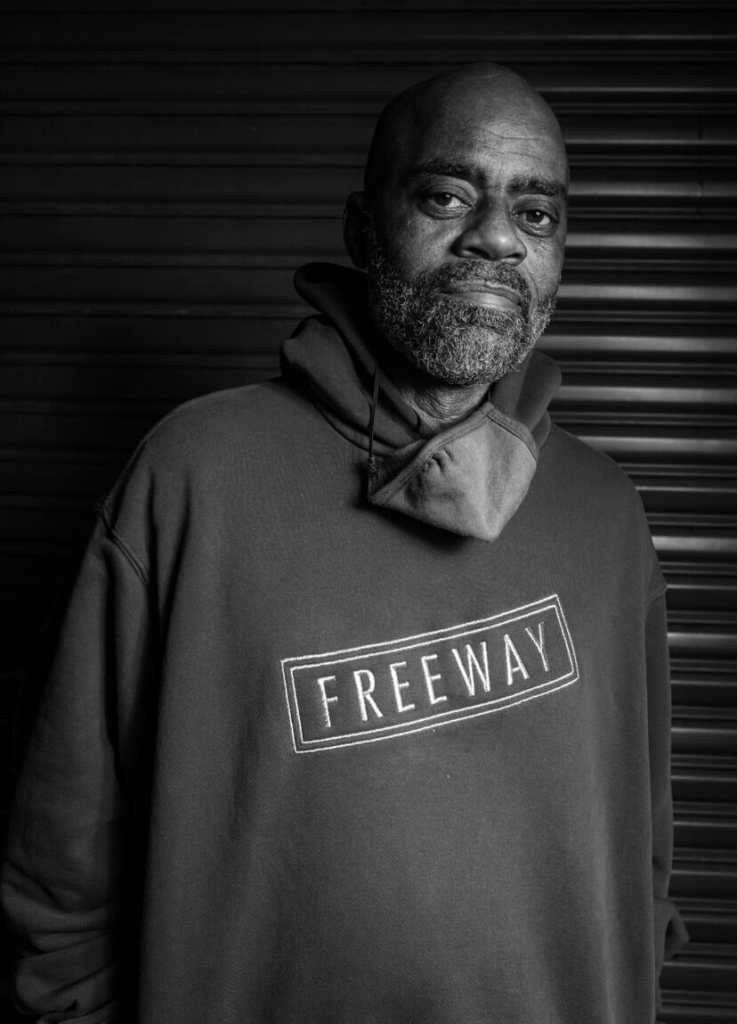

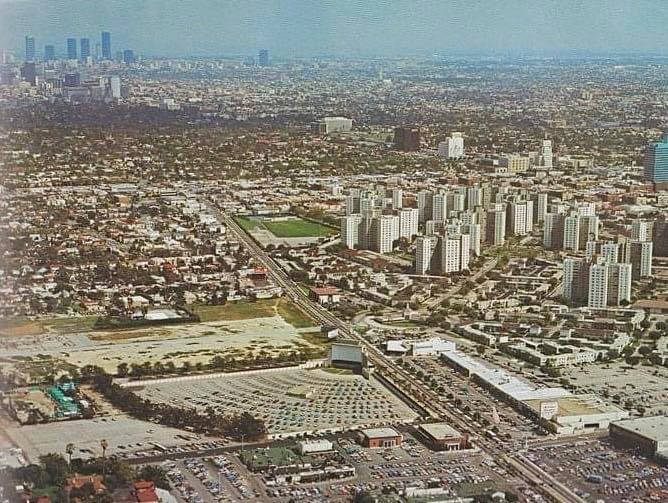

When people think of Los Angeles in the 1980s, they picture the rise of a bustling city amidst urban crisis, they picture Aids and the crack epidemic, Reaganomics and cultural paradigm shifts. The 80s were, in all aspects, a decade of economic calamity as much as of excess and extravagance. And there are very few people who moved through this world with as much savvy as Ricky Donnell Ross, who many just know by his infamous nickname – Freeway Ricky Ross. Today, sitting in a videocall in a Black hoodie and with a wide smile, Freeway Ricky Ross lives a very different life than he did half a century ago. Yet, few have shaped the Californian metropolis in the American West as much as Freeway Ricky did in those eight years that established his legacy as one of America’s most infamous former drug kingpins – so much so that the rapper Rick Ross decided to take his stagename from the original, and some say, the only real Rick Ross.

The real Rick Ross, though, is not a rapper. Today, the 66-year-old is an entrepreneur, author, community advocate, prison reform activist and sports manager. In the 80s, however, he was one of the most successful drug traffickers the city had ever seen. Federal prosecutors estimated that between 1982 and 1989, Ross bought and resold several metric tons of cocaine. In 1980 dollars, his gross earnings were said to be in excess of $900 million (equivalent to $2.7 billion in 2024) – with a profit of nearly $300 million and a distribution empire including 42 cities and thousands of employees. “I started my drug business with 125 dollars – that was all I had at the time – and I was able to turn it into sometimes three million dollars a day”, Freeway Ricky tells us.

However, building a drug empire was not at all what young Ricky had envisioned for himself as a young man. In high school, Freeway Ricky was a talented tennis player. “I just wanted to go to college and play tennis and maybe become a pro one day”, he says. But being illiterate in a public school system overwhelmed by a lack of funding and resources, by overcrowding and regulatory restraints, he did not receive a tennis scholarship, and his dream of a life as a college athlete was over before it even began. “When I look back at life, had I been able to read and write, my life would have been totally different”, Freeway Ricky ponders. “Then, when I turned 16 or 17, I probably would have been working at McDonald’s, flipping fries, and then I would eventually have gotten to the cash register, and then up to managing and then I would have probably bought the place.” All of this never happened – yet, to this day, his tennis dream has never quite left his side. “Tennis has been so important to me throughout my life. I even credit tennis with giving me my strategy for my drug career. It gave me this tenacity that you don’t quit no matter what. In tennis, you can be down to match point, and come back and win. It taught me to just keep going.”

A naive beginning with consequences

It was at a Los Angeles community college, then, that an upholstery teacher introduced him to cocaine dealing. Starting out with small amounts, his turnover quickly grew, and soon, Freeway Ricky was in business with much larger suppliers, rising up the ranks. After a few years, he was the direct customer of the Nicaraguan exile and cocaine distributor Danilo Blandón. Through his connection to Blandón, and Blandón’s supplier Norwin Meneses Cantarero, Ross was able to purchase Nicaraguan cocaine at significantly reduced rates. Ross began selling cocaine at $10,000 per kilo, a price well below average, while also distributing it to the Bloods and Crips street gangs. By 1982, Ross had received his moniker of “Freeway Ricky”, purchasing up to 1,000 pounds of cocaine a week.

Drug kingpins like Freeway Ricky and their associates like Blandón hold almost mythical spaces in society today. Their stories have been rewritten and reinvented in popular culture and shape the public imagination of clandestine worlds. Freeway Ricky, though, points out what he perceives as widespread misconceptions. “Most drug dealers are not violent. You don’t want to kill nobody when you’re selling drugs, because it brings homicide police around. And the last thing you want is police.” He blames Hollywood for what he calls mythical narratives about drug dealers that circulate. “Once you are strung out, you don’t care who you get your drugs from. But when you ask kids who first introduced them to drugs, it’s not a strange man wearing a black cape approaching them in the park. It was their mom, their dad, their brother, their cousin, their sister, their uncle, their auntie”, he says. “So many people suffer from the same thing. They feel like they’re nothing, and they don’t want to deal with the pain and the hurt that they feel inside, so they turn to drugs.”

In the face of the incredible suffering the crack cocaine pandemic has caused to thousands of people, Freeway Ricky is aware of the role he played in making the drug available to his own neighborhoods. African-American communities were hit especially hard: Between 1984 and 1989, according to a Harvard report, the homicide rate for Black males aged 14 to 17 more than doubled, and the homicide rate for Black males aged 18 to 24 increased nearly as much. During this period, the Black community also experienced a 20–100% increase in fetal death rates, low birth-weight babies, weapons arrests, and the number of children in foster care. Crack cocaine destroyed families, homes and entire neighborhoods – something Freeway Ricky never wants to happen again. “People say about me that I poisoned people. But in the 80s, I didn’t know it was poison”, he says. “The conversation about drugs was different back then. The way I was introduced to drugs, they only gave me the glamorous side. You’re gonna get a car, you gonna get a house, you get some jewelry, you gonna get a girlfriend. And you know, I wanted a girlfriend bad”, Freeway Ricky recalls. “I was a young man. I couldn’t read, couldn’t write, didn’t watch the news, so I was kind of naive to the world. I actually wanted people to do well. I did not know any better about the how.”

Coming fresh out of high school, Freeway Ricky himself was one of those people that fell through the cracks of the system. Yet, he does not put responsibility anywhere but on himself. “I don’t blame anybody. I made my choices. Nobody put a gun to my head and forced me to do what I did”, he says. “Could the blame be put on somebody? Yes. You could say, your teachers didn’t teach you how to read, your mom didn’t teach you how to read. Your dad didn’t. Your brothers didn’t. It’s plenty of blame to go around. But today, I have no regrets, only lessons. And I learned a lot of valuable lessons.”

A harsh realization

After some time in the business, the youthful naiveté with which Ricky Donnell had started out in the business faded, and a hard reality began to reveal itself as he realized the detrimental impact of drugs on his community. “It was around 1984 or 1985 that I started to feel the conflict within myself. Suddenly I heard myself saying to my associates, don’t sell drugs to my girlfriend, don’t sell drugs to my brother, to my uncle. And when I saw myself doing that, and I realized there was something wrong with it, and that’s when I said to myself, you got to quit”, Freeway Ricky recalls. “But let me tell you this, selling drugs is just as addictive as, maybe more addictive than using drugs. Because when you sell drugs, nobody ever tells you to stop. If you use drugs, your friends will say, don’t use drugs. But when you sell drugs, they’d be like, hey, can I borrow some money?”

But Freeway Ricky did stop selling drugs eventually, because of the moral conflict, he says. One year later, in 1996, Ross was sentenced to life imprisonment under the three-strikes law after being convicted for having purchased more than 100 kilograms of cocaine from a federal agent in a sting operation earlier. Yet, it was not over yet for the man who had just decided there was more in life for him than a destructive business. Having finally learned to read at the age of 28, during a first stint in prison, Ross spent much of his time behind bars studying the law. He eventually discovered a legal loophole in his case that his lawyers had overlooked. Ross’s case was brought to a federal court of appeals which found that the three-strikes law had been erroneously applied and ordered that he be resentenced. His sentence was reduced to 20 years and Ross was released from prison in 2009. That is the thing he is most proud of in his life, he says. “That I got myself out of prison. That I found the issue that eventually saved me.”

While serving his sentence, Ross dedicated himself to personal growth, education, and self-improvement. From the doors of the Federal Correctional Institution, Ross walked out an advocate against drugs and to many, as a symbol of redemption and change. Today, Ross commits to community outreach and campaigns for prison reform. “I go into prisons and I talk to the guys about how I did my time, and how they should be doing their time. I believe that one of the best ways that you can ensure that you don’t go back is becoming smart, studying”, Freeway Ricky explains. He has nothing but criticism for the American prison system. “Our prison system is not geared on rehabilitation. It’s geared on incarceration. They put people in these big warehouses, in concrete buildings, and they put bunk beds there, and they just warehouse them as if they are a product on the shelf. Inmates are like groceries in a supermarket. That’s what they do to human beings. When these people get out of jail, they’re lost because they’ve been gone for 30 years. So now they’re worse off today than when they went to prison”, he criticizes. For him, this system does not even make sense from an economic angle. “You have people there, many of whom want to do something different, and then you just don’t enable them. Here in America, they’ll pay $43,000 to keep you in prison, but they won’t pay $28,000 to give you a job.”

A CIA conspiracy?

Freeway Ricky’s story reads like an action novel – and it is all the more interesting to many for one reason: In the year 1996, a series of articles by journalist Gary Webb in the San Jose Mercury News revealed a connection between one of Ross’s cocaine sources, Danilo Blandón, and the CIA as part of the Iran–Contra affair. In his “Dark Alliance” article series, Webb examined the origins of the crack cocaine trade in Los Angeles and claimed that members of the anti-communist Contra rebels in Nicaragua had played a major role in creating the trade, using cocaine profits to finance their fight against the government in Nicaragua. It also stated that the Contras may have acted with the knowledge and protection of the CIA.

Webb was one of several writers who similarly alleged that the CIA was involved in the Nicaraguan Contras’ cocaine trafficking operations during the 1980s Nicaraguan civil war – in an effort to help finance the Contra group as it was trying to topple the revolutionary (and communist) Sandinista government.

Indeed, a 1986 investigation by a sub-committee of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (the Kerry Committee), found that “the Contra drug links included”, among other connections, “[…] payments to drug traffickers by the U.S. State Department of funds authorized by the Congress for humanitarian assistance to the Contras, in some cases after the traffickers had been indicted by federal law enforcement agencies on drug charges, in others while traffickers were under active investigation by these same agencies.”

Webb’s series revived the controversy and ultimately led to investigations by the US government, including hearings and reports by the United States House of Representatives, Senate, Department of Justice, and the CIA’s Office of the Inspector General. All of them ultimately concluded that there was no evidence of a conspiracy by CIA officials or its employees to bring drugs into the United States. The Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, and The Washington Post also launched their own research into the matter and they, too, rejected Webb’s allegations. However, an internal report issued by the CIA would admit that the agency was at least aware of Contra involvement in drug trafficking, and in some cases dissuaded the DEA and other agencies from investigating the Contra supply networks involved.

“I knew absolutely nothing about the CIA being involved when I first went to jail”, Freeway Ricky says about this. “But after, I started going down the rabbit hole. I found out that the guy I was getting my drugs from, Danilo Blandón, was a CIA operative. He worked with the CIA, he was not an agent, but he got money from the CIA. When I read that, I was blown away. You guys are paying a guy that is selling me cocaine? And he’s on your payroll?”, Ross asks.

Gary Webb, who did extensive interviews with Freeway Ricky, died of suicide in 2004. “I very much liked Gary. He had a lot of tenacity. He was just an all-around good guy, in my opinion”, Freeway Ricky remembers. He believes Webb’s findings in the article series to be correct, even though multiple parties attempted to discredit it. “They tried to make it that Gary said the CIA targeted the Black communities with the crack on purpose. That was how they wanted to spin Gary’s articles. But Gary never said that. What he said was that the cocaine went to the ghettos, not that the CIA purposely targeted the ghettos. That’s how a lot of people try to discredit his story.”

For Freeway Ricky, however, these are all stories of the past. Today, he wants to use his energy for positive change, to “make life better for everybody”, he says. Among other things, he now manages several boxers. “I once had the privilege of shaking hands with Don King, and when I went to prison and I was sitting in my cell, I was thinking, what if you’d have told Don King you had $3 million and you’d have been willing to give him all the $3 million just to take you with him. What if I had had the privilege to work with Don King before I went to jail? Would I have gone to jail? I wouldn’t.” So Freeway Ricky studied boxing in prison. “I realized, damn, boxers keep winding up broke. They make $600 million, but at the end of the day, they sit in front of some casino and try to make some money as a doorman. They need somebody to manage their money”, Ross recalls. “I am good with money. Let me manage theirs.”

It is for things like these that Freeway Ricky Ross wants to be remembered one day. “If somebody goes up to my grandkids, twenty, thirty years from now, and says, hey, your granddad sold drugs – I want them to be able to say, ah, only for eight years. Look at all the stuff he did after he sold drugs. The world was a greater place because he lived.”